For employers covered both by OSHA Recordkeeping regulations and workers’ compensation laws, it can be a challenge to determine when and where to report a work-related injury or illness. Just because you can make a workers’ comp claim doesn’t mean an incident is OSHA-reportable and vice versa.

The issue of COVID-19 is even more challenging: usually, communicable diseases (or general ‘disease of life’) aren’t reportable or covered at all. Yet, several states believe that not only is COVID-19 a workers’ compensation issue, but some states consider COVID-19 is a presumptive workplace illness. In California, it is a presumption until 2022.

When does a client need to report a COVID-19 case to OSHA, and when can they file a claim? In this post, we’re covering the disconnect between the two systems as it currently stands, so you can better support your clients as they navigate COVID-19 on their sites.

Note: The legal situation surrounding COVID-19 is rapidly evolving. We will update this article regularly. However, it’s always best to check with the CDC, OSHA, and your state and local health authorities for the most up-to-date information as it applies to your local area and industry.

Why Are There Differences in Reporting for Workers Comp and OSHA?

The reason there are so many differences between the requirements for workers’ comp and OSHA lies in the foundation of these two very different systems.

OSHA regulations typically apply to employers with more than ten employees. Almost all organizations must follow OSHA recordkeeping requirements unless they are on the list of excluded industries. Excluded industries tend to be very low risk, such as accountancy firms or shoe stores.

If covered, OSHA targets each organization equally and uses a set of regulations developed at the federal level to collect safety-relevant data and promote organizational safety, usually through issuing fines for violations. OSHA covers all workers regardless of their status, including contractors and temporary employees.

In other words, if the worker gets a paycheck, then they receive OSHA protections while at work with the exclusion of a few specific scenarios (listed below).

Workers’ compensation serves a different purpose altogether. As you know, it is a form of no-fault insurance that replaces lost wages and covers medical and rehabilitative expenses after a work-related injury or illness. A workers’ comp report focuses more on the financial aspect of the injury or illness than on the safety details, such as if a safety violation contributed to the incident.

What’s more, workers’ compensation is regulated at the state level and is usually limited to permanent employees. It won’t always cover contractors or temporary workers.

For example, your clients might have a work-related incident covering a temporary contractor that requires an OSHA incident report. However, your clients are unlikely to file a workers’ comp claim because of the employment status of the worker involved.

Counting Days Differs Between OSHA and Workers Compensation

One of the many unique aspects of COVID-19 is that it could theoretically trigger a huge number of OSHA incidents and workers’ compensation claims compared to other types of illness.

COVID-19 requires days away from work almost by default. Whether a worker is asymptomatic, experiencing mild symptoms, or battling the virus and complications, medical advice demands time in isolation when symptoms appear and/or after a confirmed COVID-19 test.

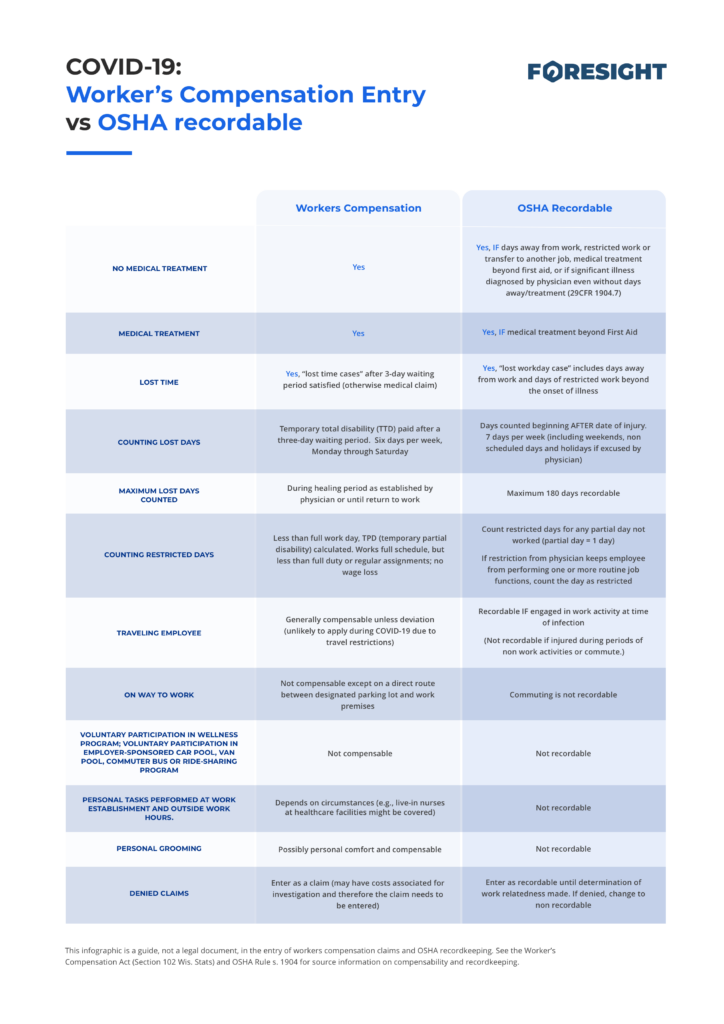

One of the best ways to see the gaps between OSHA recordable illnesses and workers’ compensation occurs when your clients need to count days away from work.

Classifying cases and counting days differs for each system, and it’s one of the many factors that could determine whether you add a case to an OSHA log, file a workers’ comp claim, neither, or both.

OSHA’s definition of “days away from work” and “job transfer or restriction” may or may not match the state’s workers’ compensation laws. For example, in a workers’ compensation claim, lost time may not exist until after a waiting period. The waiting period may or may not include the period of testing and initial quarantine after testing depending on the state’s rules.

What’s more, OSHA covers calendar days in which an employee cannot work, and workers’ compensation only covers missed workdays. OSHA also doesn’t count electing not to provide an alternative to work against the organization whereas a workers’ compensation policy might do that.

When is COVID-19 an OSHA Recordable Illness?

In April 2020, OSHA moved to compel all health care, emergency response, and correctional institution employers to record their COVID-19 cases.

At present, OSHA requires other industries to record cases unless reasonable and available objective evidence exists that the case is not work-related.

While your clients may not need to record every confirmed COVID-19 case on your log, they must investigate work-relatedness in all cases.

In the case of COVID-19, all work-related cases are recordable on the OSHA 300 log when the worker is infected as a result of work-related duties, and one or more of the following criteria are met:

- They have a significant injury or illness diagnosed by a licensed healthcare professional

- They take one or more days away from work

- They are put on restricted work

- They are transferred to another job

- They receive medical treatment beyond first aid

- They die as a result of COVID-19

Because a COVID-19 diagnosis means workers will almost inevitably take days away from work and have a formal diagnosis, the vast majority of proven work-related cases will go on OSHA 300 logs. Even when the case is mild, the recommended medical guidance tells everyone with a confirmed case to stay home from work, which means most cases will be recordable based on the days away from work criteria.

We want to reiterate that this applies to cases deemed to be work-related according to OSHA guidelines. To determine work-relatedness, your clients will need to investigate positive COVID-19 case on their worksite.

Your clients want to ensure they investigate. Investigating will help them avoid reporting COVID-19 cases that aren’t work-related and protect their incident rates. It will also help ensure they don’t hide any cases that could lead to painful OSHA fines.

To remain a trusted risk management advisor to your clients, encourage them to abide by OSHA’s reporting requirements.

Failing to record a work-related COVID-19 case could come with OSHA’s strict recordkeeping fines.

Experts say the vast majority of OSHA citations issued surrounding COVID-19 will deal with a failure to record or report an illness or failure to investigate an illness rather than safety violations.

Keep Work-Related Exclusions in Mind

Your clients should note that OSHA has ‘work-related’ exclusions that don’t require reporting, even if the infection is traced to related duties. Excluded from the “work-related” rule are the following scenarios:

- When the employee is performing personal tasks

- When the employee is participating in a volunteer activity

- When the employee is a ‘member of the public’

- When the employee suffers from idiopathic conditions (conditions or disease of unknown origins)

When Must Employers Report a COVID-19 Case to OSHA?

Remember that if a worker is hospitalized or dies as a result of work-related COVID-19, then the incident is reportable. Your clients must report a death to OSHA within 8 hours (OSHA 1904.39(b)(6)).

Employers also need to report any in-patient hospitalizations, amputations, and eye losses within 24 hours after a work-related incident.

In October, 2020, OSHA revised its COVID-19 FAQ section on employer reporting obligations for hospitalizations. The FAQ section regarding reporting now states:

Under 29 CFR 1904.39(b)(6), employers are only required to report in-patient hospitalizations to OSHA if the hospitalization “occurs within twenty-four (24) hours of the work-related incident.” For cases of COVID-19, the term “incident” means an exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the workplace. Therefore, in order to be reportable, an in-patient hospitalization due to COVID-19 must occur within 24 hours of an exposure to SARS-CoV-2 at work.

OSHA COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions

What does this mean in practice? Let’s use an example. An employee exposed to the virus at work who then attends the hospital for treatment five days after known exposure doesn’t warrant a report to OSHA. However, the case is still recordable as long as it is work-related.

However, if the employee dies of a work-related COVID-19 infection, then the employer must report the case to OSHA. Given that most deaths appear to occur 13-17 days after the onset of symptoms, most work-related COVID-19 deaths will be reportable.

The bottom line: Work-related COVID-19 cases will not always be reportable, but they will always be recordable, subject to changing OSHA guidance.

Recordable vs. Compensable: Does a Workers Compensation Claim Require OSHA Recording?

Workers’ compensation laws have no bearing on whether an organization records a COVID-19 case with OSHA and vice versa.

As we mentioned before, these are two separate sets of regulations with two distinct purposes. Each report has different standards and requirements, even when the details of the case remain the same.

Whether or not your clients can make a claim on a COVID-19 case largely depends on your state, their industry, and their policy coverage. Although there are many variables associated with workers’ comp claims, some general guidance suggests that if a client has a COVID-19 case that is demonstrably work-related, then they should file a claim.

When could a workers’ compensation claim not be OSHA recordable?

First, the exceptions listed above apply. If the employee catches COVID-19 at work while completing personal tasks, then it could be work-related and be subject to a workers’ comp claim but not necessarily be OSHA recordable.

As another example, an employee can choose to pursue a workers’ compensation claim as a result of work-related COVID-19 even if they don’t receive medical treatment beyond first aid and aren’t an OSHA recordable case.

Examples like these are bound to test the insurance industry. And in places like California and New York, these tests are already happening.

COVID-19 may not require medical treatment in every case, but it may still cause days off work. This distinction is important because the vast majority of COVID-19 cases are diagnosed and then sent home to self-quarantine and recuperate.

General guidance suggests that if a client has a COVID-19 case that is demonstrably work-related, then they should file a claim if they wish to do so.

Only the most severe cases tend to be admitted to hospitals or receive specialist care. Clients may find it’s more common for a worker to experience intense symptoms and long-term effects but never make it to a hospital. Even then, we are not yet at a point where there is enough data to safely say what the virus does to the body over the long-term, so the claims could be delayed into 2021 or beyond as knowledge of the virus grows.

Even still, the time away from work factor usually kicks in, making the case both subject to a claim and OSHA recordable.

What’s a Work-Related Illness?

Just as there are differences in the way each system counts “days away from work,” differences in work-relatedness also exist.

As noted previously, OSHA covers all workers regardless of their status when they are performing their core job duties. Workers’ compensation only applies to a select group of employees (usually permanent) but covers them in more circumstances, such as in voluntary roles and while performing personal duties at work.

In the case of COVID-19, each state may take a different position on work-relatedness. Per the National Council on Compensation Insurance, 19 states already had policies presuming respiratory illnesses were work-related and covered. These policies covered first responders, and it’s unclear if they might extend both to labor generally and to COVID-19.

Here’s how it’s shaking up in a few states:

- The burden of proof rules in Illinois and Missouri present an emergency lower burden of proof for work-relatedness for COVID-19, which is likely to increase both the claims and the severity of the claims

- CA Gov. Gavin Newsom issued an executive order issuing a rebuttable presumption that all COVID-19 illnesses arose out of employment as long as they were diagnosed within 14 days of their last day on the job. Employers can issue a rebuttal when they have evidence that the case originated elsewhere, but the executive order streamlines cases.

- Through House Bill 4749, Massachusetts could soon consider this option for certain classes of workers, like healthcare workers. If passed, medical personnel with a COVID-19 diagnosis would enter into prima facie evidence.

Even in July 2020, few states had formally issued an official stance on the issue of work-relatedness. Many bills (including MA House Bill 4749) remain stuck in committee or are still waiting for a vote to become law.

As a result, your clients will still need to investigate and it remains the employee’s obligation to prove causation at work.

Essential Exposure: Differences Between Healthcare and Other Employers

By and large, current workers’ compensation requirements only cover illnesses arising from COVID-19 when they:

- Arise from the course and scope of employment and

- Arise or are caused by conditions particular to the work

While some states may apply it regardless of work conditions, it’s likely that the vast majority of claims will be required to be unique to the employee’s work conditions. Often, it means the necessity for interacting closely with people who have tested positive for COVID-19.

For example, those working in healthcare will usually meet both requirements when it is their job to work in contact with COVID-19 patients. As a result, there’s a much lower threshold to connect a healthcare professional’s case to the course of their work. An ICU nurse working in a COVID-19 ward would have little trouble proving COVID-19 is caused by conditioners particular to their work. However, an orthopedic surgeon who is stood down or is seeing private patients in their office outside of a hospital may not be able to do so.

The vast majority of occupations will be subject to the statutory language surrounding their industry or type of employment.

In April, Kentucky became the first state to offer workers’ compensation claims to grocery store workers who test positive for COVID-19. The payments also included: Postal Service, state community-based service workers, shelter and crisis center workers, childcare providers, and health care, first responders, and military. In Kentucky, it’s thus much easier to connect a shift at a grocery store to COVID-19 exposure because grocery store workers are essential workers and their job requires interaction with the public.

When the presumptions and language do expand beyond healthcare and first responders, they do tend to be limited to the states’ ‘essential employees’. It’s unclear who and when coverage will extend to in the event of a fuller ‘re-opening’ of the economy.

What’s more, orders to protect larger swaths of workers haven’t stood for very long without a legal challenge. Illinois was the first state to place the burden of proof on the employer for essential workers, but a judge stopped enforcement saying the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Commission didn’t have the authority to make the change.

What to Remember as We Continue to Face COVID-19

As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to climb nationwide, the number of claims will be influenced by an array of factors, including but not limited to state laws, local transmission, and job-related risk.

Continue to guide your clients toward effective COVID-19 prevention. By emphasizing the hygiene and social distancing guidelines set forth by OSHA, CDC, and EEOC, you’re far less likely to find work-related cases and thus the need to navigate these claims.

If a work-related case does arise, guide your clients as they respond to new cases. Remind your clients that a workers’ comp claim is not predicated on an OSHA illness report and vice versa. There may be overlaps in reporting requirements and the incident details may remain the same, but each program has unique concerns, definitions, and reporting requirements.